Herman Van Ingelgem - Zur Gesundheit - until 8 February 026

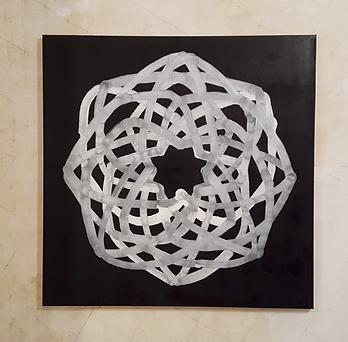

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Herman Van Ingelgem

Foreign Bodies & Protheses

06/09/2021 - 17/10/2021

Letter: to Herman Van Ingelgem

(and to the visitors to the exhibition Foreign Bodies & Prostheses)

Oh! That’s not a particularly good word to start a reflection on an exhibition. But it’s a word that’s quite suitable as a response to the crumpled thinking with which we’re so often surrounded these days. Everything becomes the object of nothing, nothing becomes the object of everything. Recently I was in Herman’s studio and we discussed the difference between things and objects.1 Two words that in an impatient way of thinking can mean the same, but if we fold open looking and thinking, differences in meaning between the words appear, no matter how slight these may be. You should try it for yourself! What’s a thing? What’s an object? Personally, I relate most to the words things, thing, thingy, thingamabob... A concrete, but indefinite reference to something that is really there. A thing is also something near us, something from our direct everyday surroundings. Anyway, the object of this letter is the exhibition Foreign Bodies & Prostheses. And this exhibition consists of things and objects that have been organized in a certain way in Annie Gentils Gallery. Herman Van Ingelgem only rarely or even not at all interferes with the objects and things in the exhibition. He brings together familiar things, puts them down, leaves them to lean or hang. Every object (or thing) is familiar and recognizable; sometimes it’s so banal that it’s hard to approach as a work of art.The artist directs the objects in space and whispers possible meanings. Doesn’t it strike you that almost all objects are empty—at the moment of the exhibition filled only with air and space? Every object reminds of an everyday action or an event that takes place at a certain moment in time; every object is the sinister witness to a ritual and mutual action performed by human beings. The exhibition Foreign Bodies & Prostheses stages emptiness with a certain discomfort. Herman Van Ingelgem causes the objects to talk, to acquire a meaning that is unrelated to their use. The sculptures are the archetypical props of a lived time, metronomes of thinking and acting. When some time ago I visited Herman in his studio, I had the privilege to see embryonic shapes that were to become the works on view at the exhibition. At the time, the works were still surrounded by the noise of the studio, the pollution of the concave and convex sides of life. Already back then, I sensed how confrontational this work was and is for me. Its leanness suffocates, while at the same time it displays the elegance of the everyday. We talked about Hannah Arendt, about death, fathers, psychoanalysis, holes and hollows, meaning and emptiness,... A few days before the opening of the exhibition, I had the privilege to see it, in the company of Chloë Op de Beeck and Annie Gentils. I had put too much sugar in my coffee. The neutral grey carpet made the gallery drift towards something else, as if nothing were on view, as I were an uninvited guest in a space that had just been abandoned. In the same way that a poem is a sequence of words, the gallery space became a spatial sequence of compound objects. Let me just pick one—an object that particularly hit me with this sense of discomfort. It’s not that I want to turn this object

into something more important with regard to the others; it’s just that I want to get nearer to that with which I already seem to be familiar. The work is an intact metal mudguard/wing that has been attached to the wall close to the ground. The metallic silver blends very well with the neutral grey of the carpet. Standing before the mudguard, you see on the right side pinkish candle grease or wax drippings on the wall and the carpet. Taking a closer look, you’ll notice there’s a pink organic growth on the inside of the thing. The mudguard is the only object in the exhibition that has come from outside and has something to do with transport. Almost effortless or without intervening, the artist succeeds in presenting a shape, with the original functionality of the object making way for a new, different meaning. This new meaning seems to elude language and description, yet it finds its way in the object’s multisemantic field. I’ve long since forgotten what Magritte has said, and in fact I even don’t want to be reminded of his words. What I want to be reminded of, is the suspense of objects—a suspense that encodes the course of life. Or do you actually remember whether there was enough sugar available?

Philippe Van Cauteren Mechelen, 25 August 2021

------------

1 Translator’s note: In Dutch, the author actually uses three words—voorwerp, object, ding—with indeed slightly different shades of meaning.

.png)

.png)