Herman Van Ingelgem - Zur Gesundheit - until 8 February 026

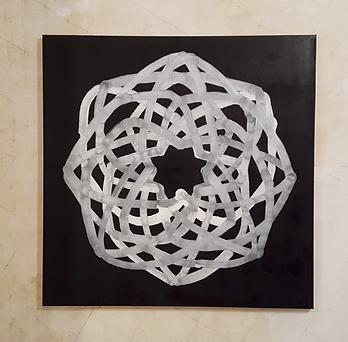

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Herman Van Ingelgem

Foreign Bodies & Protheses

06/09/2021 - 17/10/2021

STEPHEN WILLATS

Made during the extreme isolation and vacuum of London's Lockdown for the virus.

Filmed in Kodak Super 8.

One continuous car mounted shot going out of London on my main route to the West.

Text selected from a thesaurus of words associated with travelling and leaving.

Stephen Willats: a Man from the Twenty-First Century

Creating a parallel world

Stephen Willats’ studio in London is located within walking distance of the Lisson Gallery where, when I visited him for the first time at the end of last year, he had been invited to participate in a group show conceived by the artist Cory Arcangel. This confirms the interest that an artist like Stephen Willats (London, 1943) is able to arouse among younger generations of artists.

The attention for Willats has increased in particular in a period when the word Modernism –with all its implications for art, architecture and philosophy– seems to have appeared in every single art review and press release for at least the last five years. As evidence of this trend it suffices to look at the exhibitions Willats has participated in recently, such as ‘Die Moderne als Ruine’ in Vienna and ‘Modernologies’ in Barcelona. I personally became interested having seen the work ‘Wie ich meine Fluchtwege organisiere, 1979–1980’ in Vienna and I realized that, besides the critical discourse towards modernist ideals, he was a forerunner in researching and tackling the concept of ‘planning’ in architecture and design, particularly in their relationship to the individual and communities who have to live ‘within the plan’.

When walking into his studio you have to stoop to pass beneath the low door and, it may be by chance, but this physical action, which makes tangible the moment of crossing the threshold, seems to refer to one of the main issues of Willats’ research:

the relationship and communication between the outside world and ‘personal space’. A relationship that, in his understanding, goes far beyond the public -private dichotomy, and which produced a multifaceted discourse, juxtaposing what he called the planned ‘new reality’ and the people’s self-organization. The border between art

and society is the other threshold, maybe an even more important one, that he has

been stressing and blurring from the beginning of his career.

New Era

From the late ‘50s onward Stephen Willats witnessed the emergence of a built environment in London that was mirroring the economic and social growth of the period and was therefore strongly connoted by a general optimism towards the possibility of foreseeing and planning every realm of society. Nowadays it is a well documented fact that not all these promises have been kept, or that someone didn’t want to keep them, i.e. that the planned infrastructures and services needed to produce a livable social environment have slowly been withdrawn, producing isolated and depressed milieus; an urban policy that caused the stigmatization of certain peripheral areas that, in some cases, turned in real ghettos (for instance the Avondale Estate and the Skeffington Court at Hayes in the early ‘80s, both in West London). (1) But at the time it was easy to get enthusiastic about the scale and vertical projections of tower blocks that embodied the idea of a better future and a ‘new reality’ –something that Willats himself celebrated in his early drawings.

This celebration of a new era went along with Stephen Willats’ intention of challenging the role of the artist in society, and in acting outside of the designated art institutions so as to engage directly with the audience. His participation in an interdisciplinary think -thank with mathematicians, art theorists and philosophers increasingly drove him to see all art as being dependent on society and in a mutual relationship with it. A growing interest in the language of cybernetics – well documented in all the diagrams and sketches representing conceptual models of communication and exchange networks-defined his artistic practice and his conception of the artwork as “a dynamic structure of events in time, dependent on exchanges between people, reflecting their inherent relativity in perception, being tied to a context that was already meaningful to those people.” The artwork was in this sense conceived “as operating within the domain of the ‘audience’, using their language and priorities, etc.” (2) Therefore it becomes a “time-based evolving communication strategy” (3) that changes from time to time and from situation to situation according to the specificity of the environment where it is produced and to

the participants’ behaviours and responses. This kind of artistic practice, open towards the active participation of the audience, demonstrates Willats’ intentions: opposing the figure of the artist as the sole author and putting himself in a position of dependency upon the audience.

Outside/Inside

This theoretical approach to art was first implemented with the sort of sociologicalmethodology of projects such as ‘Man from the Twenty First Century’ (Nottingham,1969-1971), when Willats, with a group of students, staged a ‘man from the future’ dressed in a silver suit and with a Volkswagen camouflaged as spaceship. Questionnaires consisting of a symbolic language were distributed door to door to a working class community and to a middle-class one in order to determine lifestyle patterns, but also to facilitate communication and reciprocal understanding between the two. It is here that Willats starts to focus on the relationship between the outside, institutionalized and ruled world, and the inside, personal and creative environment. The latter was a standardized architectural units with its designed norms and slowly Willats understood the objects central role within this realm. They offered, in fact, the possibility of self-organize one’s own space through small creative acts that tend to

subvert the specification given for that space or that object. Traces of this research are still very visible in his studio nowadays where he gathers clocks, vases, lamps,etc. from that period; objects, as he said, that ‘emanate optimism’. All these issues and ‘polemics’ became clearer when he started engaging with tower blocks as the monumental symbol of the ‘new reality’; an issue that at that point needed to be discussed, especially with the people who were living in it. This challenge also brought him to explore situations in Paris (‘Les Problèmes de la Nouvelle Réalité’, 1977) and Berlin (‘The Märkisches Viertel’, 1980). From ‘Vertical Living’ (1977/78) onwards, what becomes relevant is the tension between the determinism of the concrete built environment and how the inhabitants adapt: “They found themselves in a psychological situation where they were distanced from the world outside and from the other people inside.”(4) In Willats’ interpretation, the unconscious reaction to this context is channeled via the objects and the view through the ‘picture window’ that turn into means to produce a ‘psychological link’ (5) with the world outside. This is an idea that later develops in the concept of ‘counter-consciousness’; namely, the struggle of people to express their own individual identity in a sterile and non-responsive environment. The potential creativity contained in these situations or, to paraphrase Michel de Certeau, the inventiveness of the tactics against the imposed norms, become one of the central issues in Willats’ research. The ability to escape the rigidity of real estate finds its main expression in works such as ‘Pat Purdy and the Glue Sniffers’ Camp’ (1981-82). The threshold and boundary this time takes the shape of a hole in a fence separating the tower blocks in Hayes, West London, from ‘The Lurky Place’, a wasteland where youths walk in to generate new forms of sociality that often imply the misuse of everyday objects like glue cans to get high. It is in fact in this ‘terrain vague’, with no planned destination, that the people are able to “create a parallel world”, (6) often with violent outcomes towards things and private property; an entropic means of escape that is still stigmatized as pure vandalism even today, but that in many cases it is only an automatic form of resistance that Willats names “creative behaviour”. (7)

Emanuele GUIDI

Is the editor of the book ‘Urban makers: parallel narratives on grassroots practices

and tensions’, Berlin, 2008.

(1) Willats, Stephen. Beyond the Plan, Wiley-Academy, Great Britain, 2001, p.38

(2) Willats, Stephen. Art and Social Function, 1976 Reprinted Ellipsis, London, 1999, p.8

(3) Willats, Stephen. Beyond the Plan, Wiley-Academy, Great Britain, 2001, p.10

(4) Willats, Stephen interviewed by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Abitare Magazine Website, 04.09.2009

(5) Willats, Stephen. Beyond the Plan, Wiley-Academy, Great Britain, 2001, p.22

(6) ibid, p.43

(7) ibid, p.43

.png)

.png)