Herman Van Ingelgem - Zur Gesundheit - until 8 February 026

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Marc Rossignol

Synchrone

Opening Sunday 9 September 2018

Herman Van Ingelgem

Foreign Bodies & Protheses

06/09/2021 - 17/10/2021

Hans Theys

The smallest possible circumference

A few words on the work of Guy Rombouts on the occasion of the exhibition 'Les beaux contes font les bons amis, les mots comptent pour les faux amis' at the Annie Gentils Gallery

A few years ago I heard that the famous sculptor Anthony Caro, after a visit to the M HKA, stated that he was most touched by the sculptural installation 'X of Y' (X or Y) by Guy Rombouts (b. 1949). This installation from 1985 consists of dozens, at most knee-high assemblages of three objects that together form a seventeen-meter long row. I ask Rombouts whether these objects mean something and how they met each other. "Together they form a love letter to the young Vyvy Zwevenepoel.," he says. "Because of my dissatisfaction with the regular alphabet, I felt compelled to use objects. They are objects that have found each other because they fit together in one way or another. Do you know the expression 'like a pair of pliers on a pig' (Flemish expression for: 'this makes no sense at all')? Well, they all say the opposite. The objects form trifecta because two points that are connected to each other can only form a line. Only with three points can one make a circle, a contour, a figure, an opening, a void or a volume. The work is called 'X or Y' because together they form a line that, depending on one's point of view, suggests an X- or Y-axis. The viewer, then, is the third point, so that a new, smallest possible circumference is created.'

Today, on the first floor of the gallery, we find a related work dating back to 1979. This work is derived from a try-out composition in which a series of three letter words (all Dutch verbs, conjugated in the first person singular), together form the word "I". From this, an alphabetical list of 26 three-letter words was drawn up: aai (stroke), bel (ring), col (collate), dam (draught), eet (eat), fep (drink), gom (erase), hul (wrap), ijs (ice) and so on. Each of these words is represented here by an object: a plush tiger (to stroke), a bell, two different publications of a book, a checkerboard, a bottle of gin (to drink), an eraser resting on a partially erased anatomical drawing, a bed sheet to wrap yourself in and a small freezer with a frozen soap bubble.

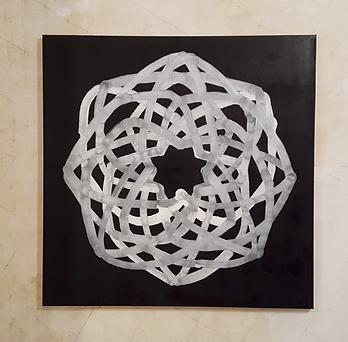

The sculpture consists of a horizontal plank that rests like a stylized cloud of smoke on three ceramic fireplaces, one of which shows bullet impacts. The cloud has the shape of the three-letter word 'NOW', which is spelled in Azart. Azart is an alphabet created by Rombouts whose letters consist of non-intersecting lines based on forms whose name starts with the same letter. The 'h', for example, has the shape of a hairpin, the 'k' has the shape of battlements or a 'keypattern' and the 'l' is lancet-shaped. Each letter was also assigned a colour, the name of which starts with that very letter. (The 'h' is represented by sky blue and 'heron blue', the 'k' by coral red and 'kelp' and the 'l' by 'lilac'.) The circumference of the wooden board consists of the 'n' of 'nijging' (Dutch: bow), the 'o' of 'ojief' (ogee) and the 'w' of 'wormstrepig' (vermiculated or wavy).

In the adjoining room we find a sculptural installation that consists of six two-meter high cabinets that are arranged in such a way that their open doors can form an enclosed space with various, adjustable compartments. In these cabinets we find different alphabets, including a colour alphabet consisting of 26 hanging shirts.

All the objects that we find here, it seems, are interesting news facts that begged to be placed in a meaningful context. Once they drew Rombouts' attention and were adopted, cherished and arranged by him. Sculpting is arranging: the creation of a visual and tactile rhythm that is characteristic of the artist. Objects, materials and techniques are used improperly, they are cherished and respected, but also misused, detached, turned upside down, cut into two and otherwise glued together. This is how the artist opens up reality. He or she looks for the seams, there is pulling, there is stitching, grids are put together: collections of holes and bumps, fullness and emptiness, absence and presence.

While we sit and talk on the first spring night, on a terrace whose one half is tiled with square tiles and the other half with the fragments that broke off when the tiles were cut (and which were collected by Rombouts), the artist cuts with an age-old cleaver the edges off of hollowed out, burning candles to place them around the big wick of an exhausted candle so as to keep the fire going. While I look at this alchemical scene, I remember that fire is the father of all things, because we ourselves are slow fires, and because all that lives is a slow fire, and because everything revolves and turns and changes, and that these endless transformations of matter are uncovered in sculpture, and that this is why its productions sometimes move us so much.

Montagne de Miel, March 30, 2018

.png)

.png)